970x125

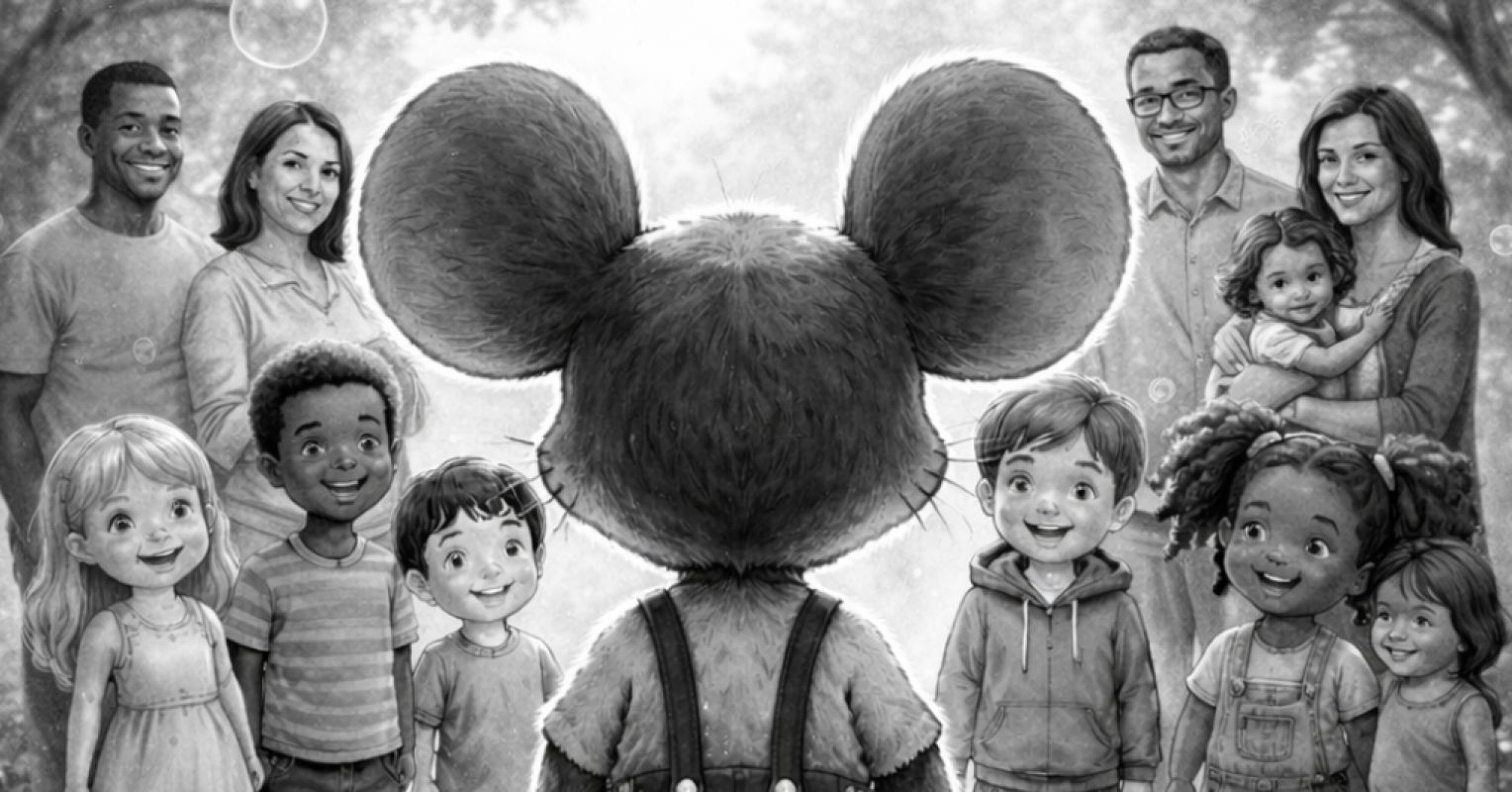

Mickey Mouse is more than a simple animated character. He represents a particular emotion that most people experience before they have a chance to process what they’ve seen. From Mickey Mouse’s two black dots for his ears, his round-shaped head, his big doe-like eyes, and his expressionless smile, it is clear that one can understand Mickey Mouse without being told anything about him.

The design of Mickey Mouse conveys specific universal characteristics that allow easy recognition from the least desirable location within a noisy movie theater (typically, the back row). In part, that recognizability has been achieved through careful choices about how to represent Mickey Mouse. The geometric shape of Mickey’s face (rounded) and large eyes are indicative of the infant stage of development, which makes him appear forgiving and approachable, as well as signaling his harmlessness.

From an evolutionary standpoint, human beings developed the capacity to recognize an infant’s ability to communicate and defend themselves. The use of large eyes and a small nose is a universal feature shared across cultures. It elicits feelings of warmth and parental care towards the baby from the adult. Therefore, when we react positively to Mickey Mouse, we are activating a robust biological response.

There is also scientific evidence to support these arguments. Numerous studies have shown that humans respond positively towards baby-like characteristics (such as baby schema features) even when these features appear in drawings rather than real human faces (Glocker et al., 2009). Mickey Mouse looks friendly to humans not only because of the way that he looks, but because Mickey activates a profound and direct biological response within humans

Make-Believe as a Survival Skill

Make-believe often gets treated as something we’re supposed to outgrow, something sweet but unserious. In reality, pretending is serious business for a social species like ours. Imagination lets us practice life without paying the full price. We rehearse danger, cooperation, loss, and hope in a safer space.

Kids playfully express their creativity, while adults utilize a more formal medium to create their own stories. Mickey is between children’s physical ability and adult storytelling methods. He experiences all of life’s ups and downs; he loses, becomes frightened, recovers, but continues to move forward. Bad things happen to Mickey, but they don’t turn into tragedy or despair. This is very significant.

In terms of evolution, imagination is the method through which we, as human beings, learn to manage the stress of the unknown. The stories we tell help us identify and develop the patterns involved in solving problems as they present themselves, as well as the outcomes of each step in their resolution. Mickey provides an avenue for our emotions to practice and to develop awareness of the experience of relief.

That’s why people keep coming back to familiar characters during hard times. During wars, economic collapse, and personal grief, Mickey didn’t disappear. He became more critical. This isn’t because people were naïve or trying to hide from reality. It’s because they were regulating themselves.

Research on pretend play shows that imagining alternatives strengthens emotional control and social understanding (Lillard et al., 2013). The exact basic mechanism carries into adulthood. When we revisit Mickey, we’re not checking out. We’re taking a brief walk through a world that reminds us that resolution is possible.

Growing Up Without Growing Old

Mickey Mouse has undergone several iterations over the many years since his creation. However, he has changed, becoming a kinder and gentler character rather than the mischievous and impulsive one he was portrayed as in the early years of his creation. The change in character mirrors a general cultural trend toward stability rather than chaos, as the world has gotten increasingly chaotic and noisy. Throughout the years, the demand for Mickey Mouse has also changed. As the world became more complicated and disorganized, people wanted to be comforted by their icons and not be provoked.

Imagination Essential Reads

However, despite the world around Mickey Mouse changing, he still remains a constant through the many years people have enjoyed watching him. What is important about Mickey Mouse’s lack of age is that he can provide a stable emotional anchor throughout the years. People will continue to be comforted by him regardless of the many changes their lives have experienced. Psychologists call this phenomenon nostalgic continuity. It allows an individual to view his or her life as a single, cohesive experience that connects all its various aspects.

Nostalgia is not just a feeling someone has at a certain time, but a valid way of using feelings from the past to support someone emotionally, positively affecting their mood, giving them meaning, and enhancing their ability to connect with others when they are feeling socially isolated (Sedikides et al., 2008). Mickey Mouse allows people to hold on to their childhood memories and experiences without pressure to return to childhood. He gives adults permission to carry a piece of their childhood with them and to recall joyful memories. It is important to note that Mickey offers a place of softness and joy while still being responsible and competent.

Why Belief Never Neally Leaves Us

As beings naturally disposed to belief, we seek out signs of intent, agency, and narrative—even when they’re absent. This characteristic has been ingrained into the human psyche, likely through evolution. It is better for mankind to have a fictional thought of intent and to offer too much courtesy or loyalty than to miss an indication of danger altogether. Through generations of practice, our instinct to attribute lifelike qualities to inanimate objects has developed. We whisper sweet nothings to our animals, we have names for our vehicles, and there are many who show extreme loyalty to made-up people in books, movies, and games. Mickey feels present because our minds are designed to make him so.

Cognitive science supports the idea that imagining moral and emotional agents provides the basis for organization within our mental and emotional worlds (Barrett, 2004). It is through these agents that we hold our values close to us. Mickey exemplifies a composite of the best characteristics of hope and optimism, as well as the ability to bounce back from adversity without losing his zest for life. He has the ability to remain both playful and resilient, depending on the situation. As such, he will continue to be with us.

Encouraging play and pretend is about retaining the idea of something that is true regarding our human existence and being. Humans do not function solely on reason. We exist on multiple levels of meaning. Both physical and emotional resources sustain us. The reason Mickey is still a part of our lives today is that he is exactly where evolution has brought us. We exist somewhere between instinct and narrative.