970x125

The World Health Organization describes wellness as not merely the absence of disease, but rather a state that transcends the absence of disease and approaches optimum psychological, physical, spiritual, and social health. The history of optimizing health dates to the ancient Greeks. The fifth-century B.C. text On Regimen, authored by Hippocrates and his students, is likely the authoritative reference that described specific means of obtaining optimum health.

The modern era of wellness can be traced to Jonas Salk’s 1973 groundbreaking treatise, Survival of the Wisest. In that book, Salk defined the pursuit of health in two epochs. Epoch A was the pursuit of the absence of disease—health. Epoch B was defined as the pursuit of optimum health, a condition far beyond the mere absence of illness—wellness.

In 1978, Daniel Girdano and I authored the first widely marketed stress management textbook for colleges. Now in its ninth edition and in print for 47 years, Controlling Stress and Tension: A Holistic Approach (Prentice-Hall) was a prescriptive approach to wellness, but it somewhat narrowly focused on managing stress as the key element. In 1977, Jim Fixx authored The Complete Book of Running (Random House). Although a national best-seller, once again it had a very narrow focus. In 1985, Robert Feldman and I wrote Occupational Health Promotion (John Wiley), which was the first college text on designing and implementing wellness programs in occupational settings. Although it took a multicomponent approach, it lacked an overarching integrating framework for wellness.

Each of these pioneering books viewed optimizing the functional integrity of psychological, physical, spiritual, and social health as its goals, with the latter three breaking wellness into functional components. But one other pioneering text had the courage to break through the glass ceiling of compartmentalized functional health as a goal and dared to suggest that a more holistic goal should be pursued—longevity. The authors asserted that life could be extended by slowing down the aging process. The 850-page book Life Extension (Warner), by Durk Pearson and Sandy Shaw, was published in 1982. The book asserted that free radicals are a primary cause of aging, and it argued that aging could be slowed, and life could be extended, by the use of antioxidant supplements and other lifestyle interventions.

Free radicals are molecules with unbonded electrons. The unbonded electrons create molecular instability as they scavenge electrons from other molecules, creating oxidative stress. Free radicals are the natural by-products of metabolism, but can also be created by lifestyle (smoking, alcohol) and certain environmental exposures (pollution). The homogenizing theme in this approach to wellness by Pearson and Shaw was largely mobilizing antioxidant mechanisms as a means of achieving wellness. Antioxidants donate electrons and stabilize the molecules, reducing oxidative stress. Fast forward more than 40 years, and another more robust and fundamental homogenizing theme has emerged…an anti-aging approach to wellness that focuses on genetic dynamics.

Aging

In 1905, Einstein’s special relativity theory asserted that time could be slowed. Subsequent research has proven Einstein correct by verifying a process known as time dilation. The process of time dilation offers no practical applications at this point, however. But time dilation begs the question: If time can be slowed, can the aging process be slowed?

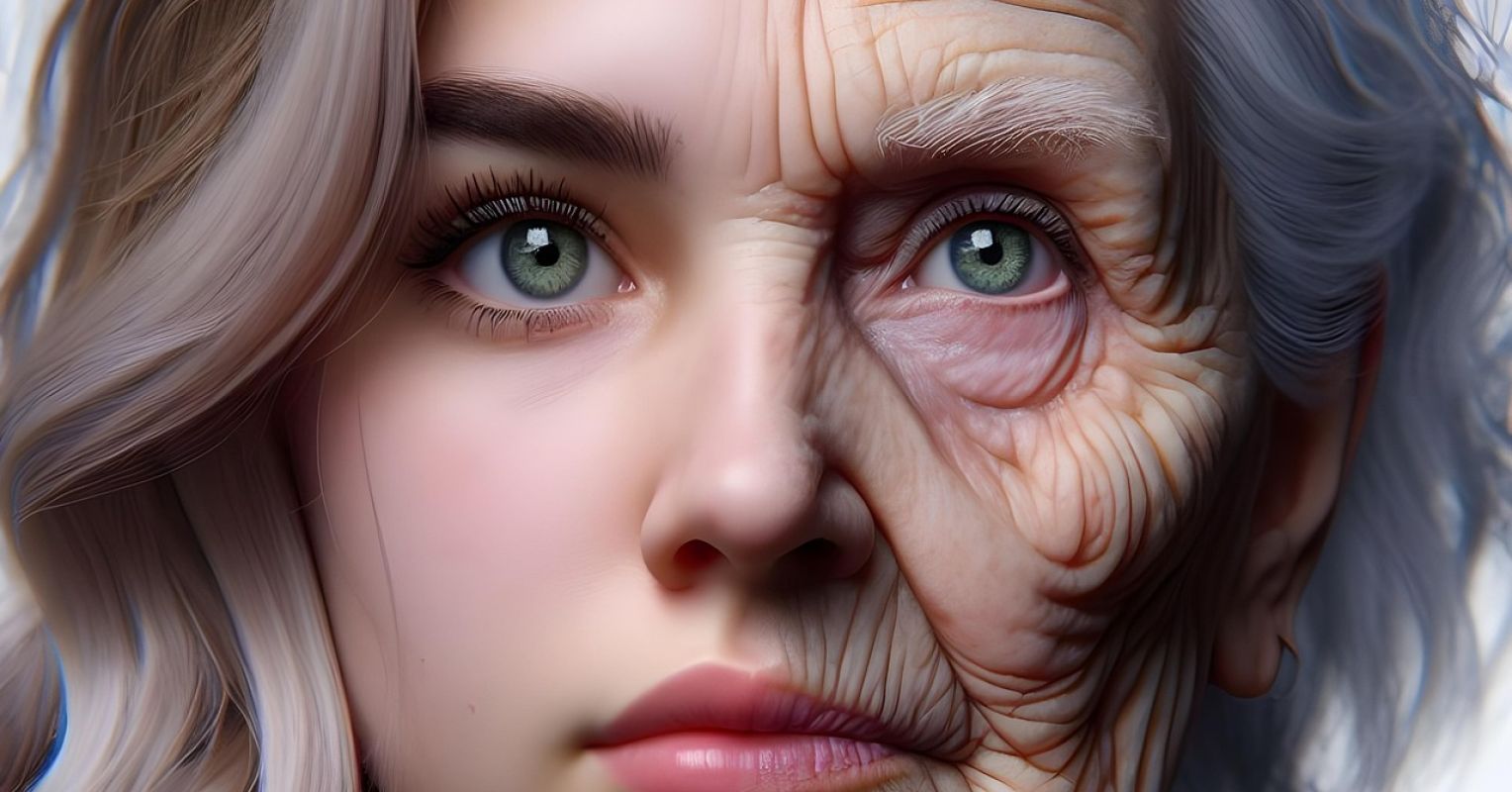

Each of us has two ages—our calendar age and our biological age. The calendar age is typically measured in the passage of calendar years. And most would agree, practically speaking, that our calendar age cannot be altered. But what about biological age? Calculation of biological age centers on the nucleus of the living cell. Inside every cell in the human body, there is a nucleus. Think of it as a command center telling the cell how to behave. Within the nucleus, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes. Each chromosome is made up of a single, continuous strand of DNA. DNA is made up of genetic segments that dictate factors of genetic expression, such as hair color, height, risk for illnesses, and the like. At the end of each DNA strand is a protective covering on the chromosome called a telomere.

There are two popular ways of measuring biological age, and both involve the telomere: 1) telomere length, and 2) DNA methylation. Each time a cell divides, its telomeres shorten slightly. Over time, the telomeres become too short to protect the DNA, which leads to cellular aging, chromosomal instability, increased risk of mutation, senescence, and ultimately death. Telomere shortening and attrition are considered a primary hallmark of aging (Lopez-Otin et al., 2023; Kmiołek et al., 2023). Methylation of DNA refers to the process of adding a methyl group (CH3) to specific spots on the DNA molecule. It provides stability to the DNA. As we age, DNA methylation becomes unstable with global hypomethylation. This instability can lead to potential mutations and reduced anti-inflammatory and tumor suppression activity. DNA methylation is sometimes used as a proxy for telomere length. The good news is that research has demonstrated that both DNA methylation and telomere length itself can be altered to potentially 1) reduce the risk of disease and 2) in the best-case scenario, actually approximate a slowing of the biological clock of aging (Espinosa-Otalora et al., 2021; Boccardi, 2025; Ornish et al., 2008; Ornish, Lin, Chan et al., 2013).

The Science of Slowing the Aging Process

A review of relevant research concluded that shortening of telomeres is strongly associated with increased risk of age-related diseases, including cardiovascular disease, neurodegeneration, and certain cancers (though a curvilinear relationship exists in the latter case). In fact, an NIH study (NIH, 2025) using Bayesian network analysis revealed that telomere length and factors such as DNA methylation acceleration independently predict mortality in U.S. adults. A cross-sectional study involving 123 older adults found that global DNA methylation and telomere shortening were associated with accelerated sarcopenia and frailty syndrome (Kmiołek et al., 2023). Conversely, a meta-analysis found that an increase in telomere length was associated with a 20 to 30 percent reduction in all-cause mortality risk (Mons et al., 2017). Translating from animal research, a landmark study on telomere length (Heidinger et al., 2012) showed that individuals with longer telomeres in early life may live up to 20 percent longer than their counterparts. Thus, reducing telomere attrition could potentially extend lifespan by four to eight years, based on current epidemiological models and longitudinal studies, though causality has not been generally recognized.

Science has identified numerous behavioral factors that both positively and negatively affect the maintenance of telomeres. As such, this list just might be a wellness guide to reducing the risk of harmful, behaviorally induced genetic mutation and perhaps even slowing down the aging process at the cellular level (Ornish et al., 2008; Ornish, Lin, Chan et al., 2013; Qiao, Jiang, & Li, 2020; D’Angelo, 2023).

If indeed there are age extension benefits—either through risk reduction or actual slowing of the biological clock—the gains could be significant. They are estimated as being 1.5 years to 8 years of added longevity when compared to the general population (See Boccardi, 2025; Huang, Huang, Lu et al., 2025; Szyf, Tang, Hill, & Musci, 2016; Ornish, Lin, Daubenmier, 2008; Ornish, Lin, Chan et al., 2013).

Factors that appear to be associated with an adverse effect on the protective telomeric caps on DNA are:

- Tobacco smoking

- Alcohol consumption

- Irregular, unrestful sleep patterns

Factors that appear to be correlated with healthy maintenance of the telomeres are:

- Moderate physical exercise

- Polyphenols

- NAD+ (a coenzyme involved with metabolism)

- Omega-3 fatty acids

- The practice of mindfulness or meditation

- Stress management

Approaching wellness through a piecemeal approach can no doubt be effective, but not necessarily efficient. Interventions that target the most robust underlying processes of health and wellness, e.g., aging, seem a worthwhile course to pursue.

© George S. Everly, Jr., PhD, 2025