970x125

Unlike gamification, where game elements are incorporated into real-world activities, the idea of serious games is to use entire games directly to solve serious problems.

The most famous example is FoldIt, in which players fold virtual proteins, watching scores fluctuate as they try to achieve some scientific goal. In 2011, FoldIt players solved the structure of an enzyme that the AIDS virus needs to reproduce, enabling researchers to develop drugs that target it.

If you ask me, the three most serious problems facing humanity today are climate change, wealth inequality, and political polarization. In that order.

If we don’t solve climate change, nothing else will matter. It’s not a “yes/no” proposition, so much as a matter of degree—the more we do, the better the eventual outcome will be, but our current trajectory doesn’t look good. At best, the future will be a less hospitable place for our children and grandchildren.

Meanwhile, in most developed nations, soaring wealth inequality is providing fertile soil for nationalism and fascist movements to fester. The super-rich outcompete everyone else for assets, pushing up costs and driving governments deeper into debt. Sadly, the fact that it’s as bad as it is makes doing anything about it tricky, due to how it poisons politics.

Exacerbating both these problems is the fact that politics has become so vitriolic that constructive discussion between opposing camps is all but impossible. Wealth inequality is unavoidably political, and although climate change shouldn’t be a partisan issue, unfortunately, it’s become one. Progress on either is therefore stymied by heated disagreement. To make matters worse, these problems are intertwined. For instance, studies suggest that wealth inequality is one factor driving polarization.

But wait, these are really serious problems, I hear you say. Surely games have nothing to contribute on such weighty matters? That’s not true. Let me explain:

Climate Change

You might think climate change is tricky to tackle via the medium of games, but numerous games that help in various ways already exist. Daybreak, for instance, is a collaborative board game in which players take the roles of major nations, aiming to reach zero emissions before the planet warms by 2 degrees. Carbon City Zero poses a similar challenge, but for building net-zero cities. These games teach players about the complexity of the problem and potential mitigation strategies, enabling them to carry lessons learned into their real lives.

Game Changers was an online story-based game mixing elements of gaming, theater, and film into an immersive narrative intended to encourage conversations and inspire action. Interactive elements, including collective decision-making, enabled players to learn about and discuss climate change.

There are also card games and video games, including FutureGuessr, an online game launched last June. Players view 360-degree panoramas of what landscapes may look like in 2100 due to climate change and have to guess the location. They’re told how close they were, shown real and predicted pictures alongside each other, and can read about the consequences if no action is taken, as well as what could be done. This avoids presenting climate change as inevitable but, rather, as a consequence of decisions taken now.

The game uses images created by a generative AI model trained on a combination of maps, photographs, and data from IPCC reports. A “take action” link takes you to the website of Résau Action Climat, the NGO network that co-developed the game.

Wealth Inequality

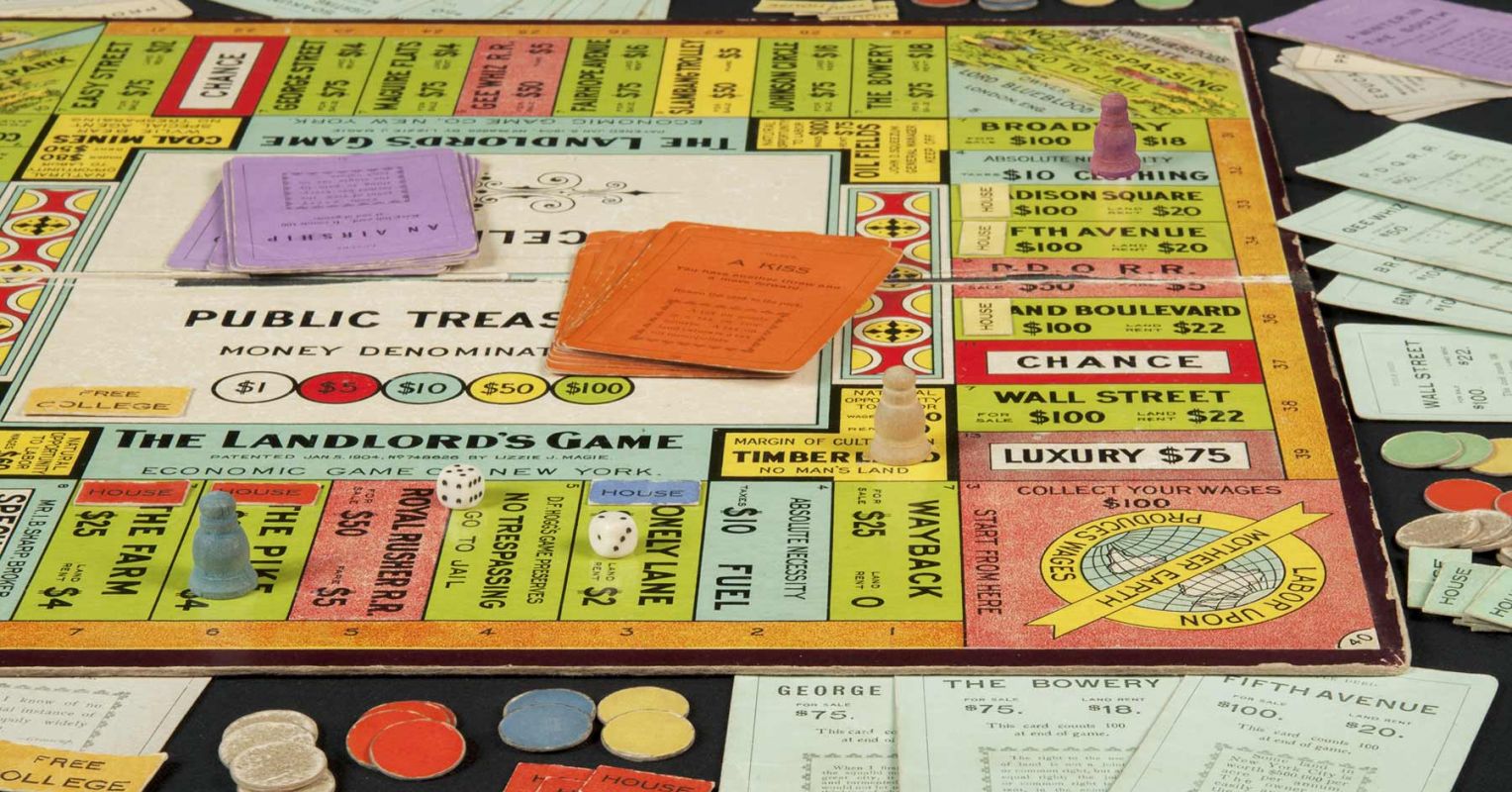

One of the first serious games went on to become a household name. What we now know as Monopoly was first conceived in 1902 by writer and designer Elizabeth Magie. She called it The Landlord’s Game and created two rulesets: an “anti-monopolist” version where players win collectively via a land tax that leads to prosperity for all, and a “monopolist” version where one player wins by bankrupting everybody else.

Magie intended the game as a practical demonstration of the problems of unrestrained rentier capitalism, hoping players would internalize the lesson, but life had other plans. Charles Darrow, a radiator salesman in Philadelphia, was introduced to the game by friends. Darrow asked his friend to write up the rules, sold it to Parker Brothers, and the royalties made him wealthy. When Monopoly took off in the 1930s, Parker Brothers hoovered up the rights to other related games. They paid Magie $500 (and zero royalties) for the patent to The Landlord’s Game.

As you may have noticed, Parker Brothers’ game makes no mention of any anti-monopolist rules. The Landlord’s Game was lost to history until 1973, when Parker Brothers initiated a legal battle with Ralph Anspach, an academic who created an anti-monopoly game, issuing him with cease-and-desist orders.

In researching his case, Anspach unearthed Magie’s story, and the resulting publicity shone a spotlight on the first serious game to tackle inequality. There have been others since, from teaching exercises to online simulators and board games. One student thesis even revisited The Landlord’s Game to study the impact of various taxes on inequality.

The Landlord’s Game can be seen as an early warning about runaway inequality, created near the start of the 20th century, which is how far back you have to go to find inequality as bad as it is today (at least within countries).

Political Polarization

Increasing polarization is threatening democracy, especially in the United States. To combat this, researchers at Harvard University developed an online quiz game called Tango, which pairs Democrats and Republicans together in teams. Different questions are designed to give an advantage to members of one or the other camp. Some probe contentious partisan beliefs, so that common views are challenged, but bipartisanship benefits the team collectively.

The study, published last June, manipulates the dimension of competition versus cooperation in games to try to forge bonds across a divide that has become notoriously difficult to bridge.

The researchers conducted five experiments, involving nearly 4,500 participants. They found that playing for just an hour reduced negative partisanship, increased warmth and generosity toward, and improved perceptions of members of the other political tribe. The results also suggest the game improves attitudes toward democracy, with effects lasting at least a month. Participants reported enjoying the game and wanting to play again.

As well as online sessions, the team envisages people encountering the game on nights out at their local bar. They recently completed a trial with employees of a large company and are customizing Tango for other countries, including Israel, India, and Northern Ireland.

The Big Picture

None of these games are attempts to solve the issue by themselves. These problems have no single solution; they can only be mitigated by broad efforts, tackling different facets, in multiple ways.

Games are especially good for education, as they go beyond just providing information to powerfully demonstrate principles, strategies, or outcomes in ways that stick with people. Participation and storytelling are powerful tools.

Some go beyond that, though, to make a difference directly, as illustrated by the last example. Tango won’t solve the problem of polarization by itself, but it’s a start, and if we make progress there, it might get easier to make progress elsewhere. After all, these issues are interlinked.