970x125

Imagine going to the doctor for a minor problem, like weakness in your leg, and you are told that 90 percent of your brain is missing. Sound impossible? It happened to a 44-year-old French civil servant. This case, and others like it, challenge everything we thought we knew about the brain’s role in human consciousness and intelligence. Perhaps the most interesting question isn’t how someone can function without a brain, but rather, where else might intelligence reside in the human body?

When Less Brain Means More Questions

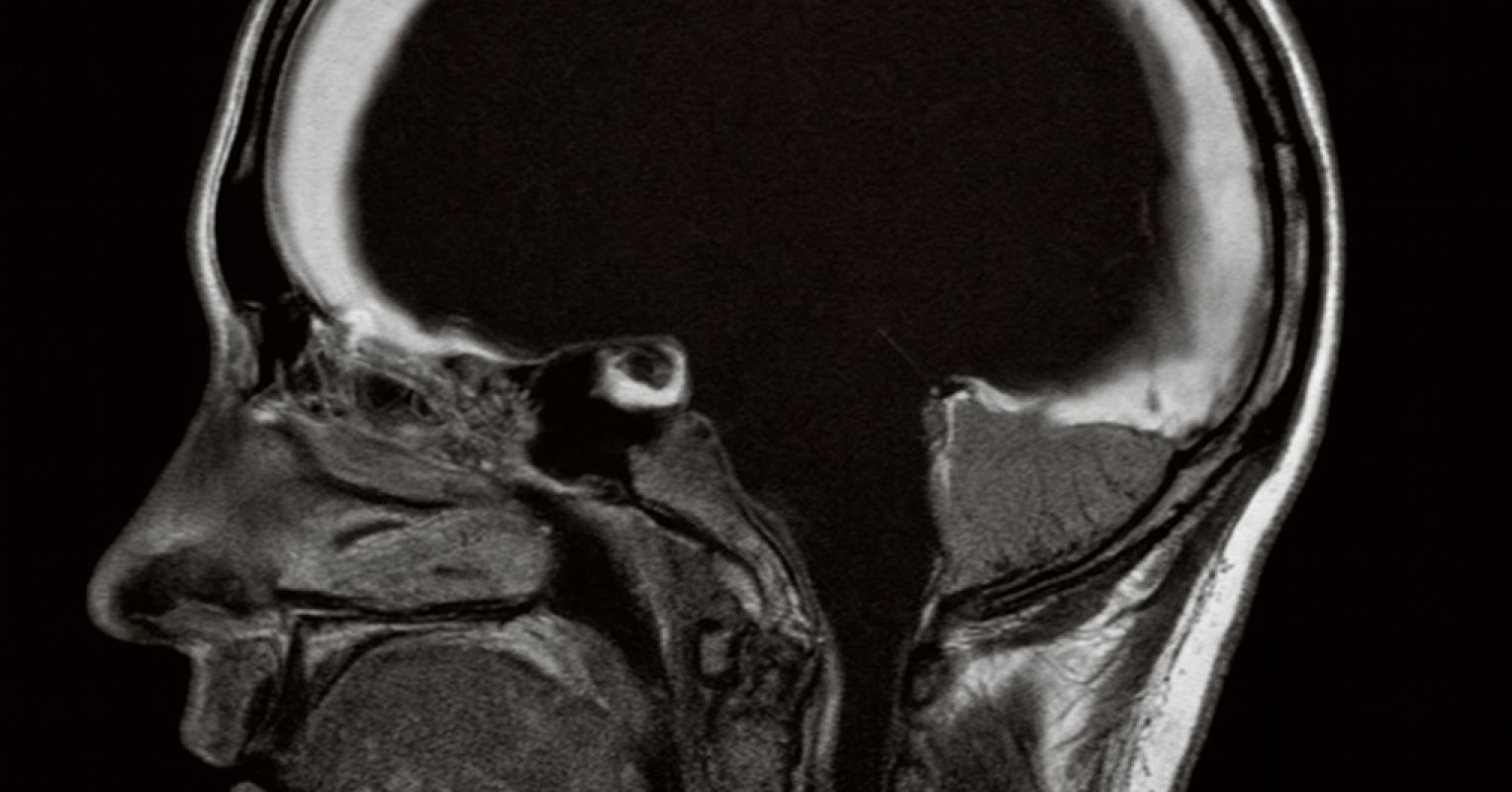

In 2007, researchers published a fascinating case report in the medical journal The Lancet. The patient was a married father of two who worked as a civil servant. His life appeared to be normal, despite the fact that he had severe hydrocephalus, a condition that involves a buildup of fluid in the brain, resulting in the brain being squeezed into very thin layers.

This civil servant’s brain scans showed he had only a very thin layer of brain tissue. His IQ was tested and was found to be 75, which is below average but is still within the normal range. Although he was not brilliant, he functioned well enough to maintain a job, relationships, and a family.

But this wasn’t an isolated case. The story continues with British pediatrician John Lorber, who in the 1980s reported an equally fascinating case.

The Mathematics Student With “No Brain”

Lorber’s case involved a mathematics student at Sheffield University who had an IQ of 126, which is well above average, and graduated with first-class honors. When he was examined, the student was found to have such severe hydrocephalus that his brain was compressed to less than 1mm thick, which is similar to the thickness of a penny, as opposed to the normal thickness of the brain, which is 45 times greater. Lorber documented over 600 cases of hydrocephalus and found that while many patients with similar findings were severely disabled, others had IQs over 100, despite having 95 percent of their skull filled with fluid.

The Woman Who Lived Without a Cerebellum

Equally remarkable is the story of a 24-year-old Chinese woman who in 2014 discovered that she had been born without a cerebellum. This brain structure contains up to 50 percent of the brain’s total neurons and controls balance, coordination, and motor learning. She became only the ninth known person to survive into adulthood without a cerebellum.

Despite lacking this important part of the brain, she managed to live a relatively normal life. She was married with a daughter, she worked, and she functioned independently. Although she didn’t walk until she was 7 years old and her speech wasn’t intelligible until she was 6 years old, she had adapted remarkably well. Her only symptoms were mild unsteadiness when she walked, slightly slurred speech, and an inability to run or jump. These deficits are far less severe than would typically be expected in an individual without a cerebellum.

Brain scans showed a large cavity filled with cerebrospinal fluid where her cerebellum should have been.

These findings led Lorber to ask the question: “Is your brain really necessary?”

The Body’s Hidden Intelligence Networks

Emerging evidence suggests intelligence and memory might be distributed throughout the body in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

The Heart’s Little Brain

The human heart contains approximately 40,000 neurons, which are referred to as the “intrinsic cardiac nervous system.” This system consists of sensory nerves that contribute to decision-making as well as short-term and long-term memory.

This intrinsic cardiac nervous system, which is also sometimes referred to as the “little brain” of the heart, makes continuous adjustments in cardiac activity through a network of neurons that communicate with each other. Recent research suggests this cardiac neural network doesn’t just regulate our heartbeat. It may also participate in cognitive processing and emotional regulation.

The Gut’s Second Brain

Another remarkable extra-cerebral nervous system lies in our digestive tract. The enteric nervous system (ENS) consists of more than 200 to 600 million nerve cells that line the gastrointestinal tract.

This “second brain” shows evidence of various forms of learning, including habituation, sensitization, and conditioned behavior. The ENS can operate independently, making decisions and processing information without needing input from the brain.

Research reveals that the gut microbiota interacts with the central nervous system by regulating brain chemistry and influencing systems that are associated with stress response, anxiety, and memory function.

Mitochondrial Memory

Inside nearly every cell in the body are hundreds to thousands of mitochondria—tiny organelles that were once considered simply as “cellular powerhouses.” But recent research has demonstrated that these structures function as sophisticated memory storage systems. Scientists have discovered that physicochemical changes of mitochondrial networks caused by transient stress create what are called “mitoengrams,” a form of cellular memory that can persist across generations.

This demonstrates that mitochondrial networks don’t just provide energy; they regulate fundamental aspects of brain function and cognition. When hydrocephalus compresses brain tissue, perhaps functional mitochondria throughout the body’s trillions of cells continue processing and storing information, maintaining cognitive abilities through distributed cellular intelligence.

Recent research has established a causal link between mitochondrial dysfunction and the cognitive symptoms that are associated with neurodegenerative diseases. This suggests these organelles play a far more important role in consciousness than was previously imagined.

The Bigger Picture

These remarkable cases remind us that consciousness may be far more distributed and resilient than we ever imagined. They suggest human intelligence may not reside in a single organ but rather may emerge from a complex system of cellular, mitochondrial, cardiac, and enteric intelligence networks working in concert. They indicate that our bodies contain multiple, interconnected intelligence networks, each capable of contributing to our human experience of consciousness.