970x125

What began as an unexpected observation and “side effect” of some medications converged with decades of addiction neuroscience: GLP-1 receptor agonist medications like Ozempic apparently reduce alcohol craving, drinking intensity, and relapses.

If you or someone close to you struggles with alcohol use, it may help to know that medication originally developed for diabetes and obesity—semaglutide or other glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists—may one day become a treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD). Not only may there be a new pharmacotherapy for AUD, but the success of these drugs forces a reconceptualization of addiction itself. This means AUD is not just a disease of the brain, but the gut may be involved too.

For 40+ years, my work and that of others supported the view that addiction is a disorder of maladaptive dopaminergic learning. Our understanding was that drugs of abuse hijacked parts of the brain. The model wasn’t wrong, but was incomplete.

Emerging evidence now shows addiction isn’t exclusively a disorder of synapses and dopamine. Instead, addiction involves many systems, including gut sensory signaling, endocrine modulation, immune tone, microbiome-dependent stress regulation, and central reward circuitry. This has been reinforced by anti-addiction findings for GLP-1s.

GLP-1 Signaling at the Intersection of Metabolism and Reward

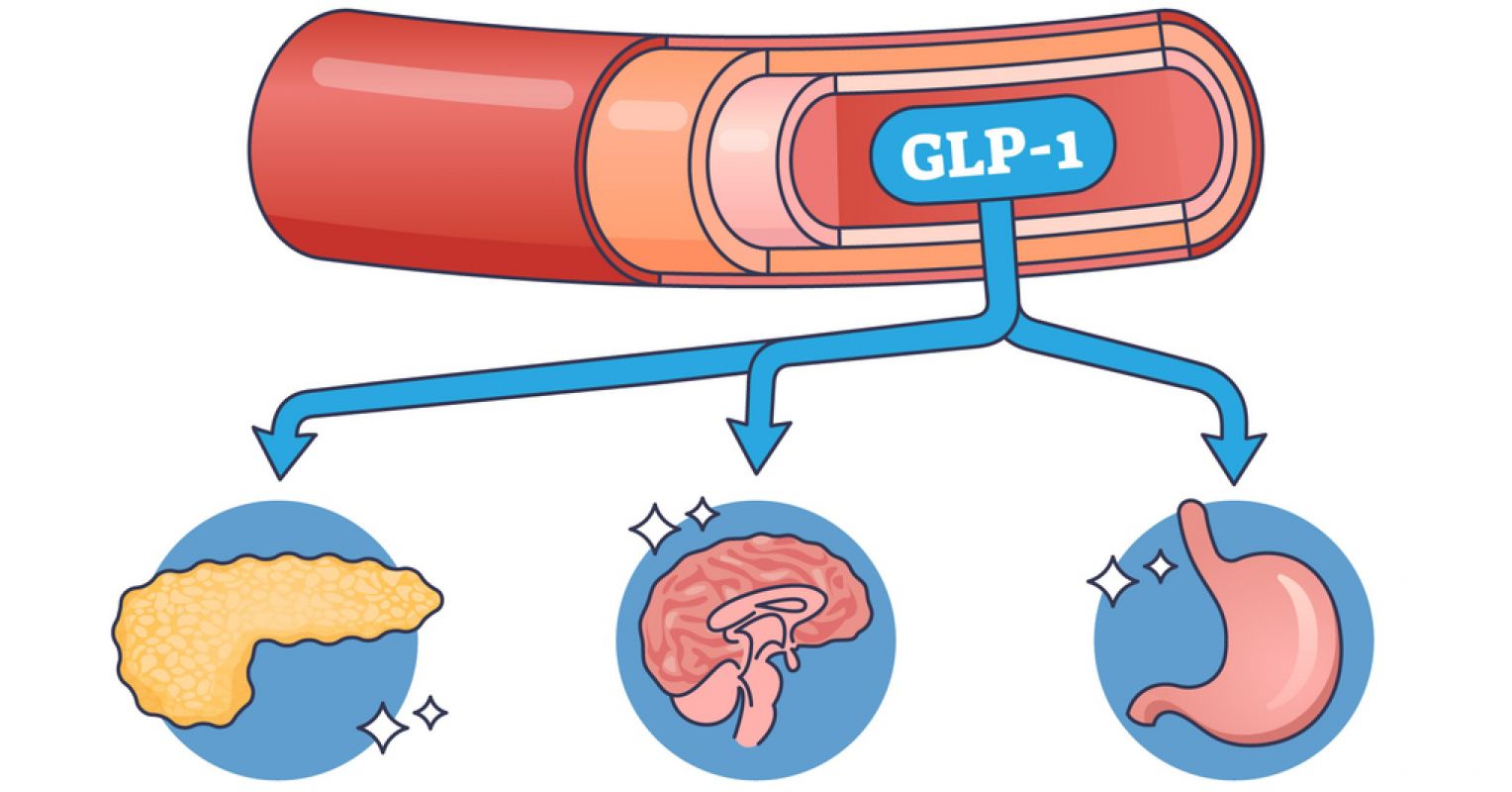

The gut and brain communicate via the vagus nerve, so gut health directly impacts mood, anxiety, and neurodegenerative conditions. In addition, gut microbes trigger the release of substances that travel to the brain and influence it. GLP-1 itself is a gut-derived incretin hormone released by the enteroendocrine cells in response to nutrient intake. Its classical functions are slowing gastric emptying, enhancing insulin secretion, and boosting satiety (feeling full). Over the past decade, studies have shown GLP-1 receptor agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic or Wegovy) reduce food seeking, but also alcohol intake, cocaine reward, nicotine self-administration, and relapse-like behavior spanning multiple drug classes.

What wasn’t initially realized is that GLP-1 receptors are also found in brain regions governing motivation and reward, including the nucleus accumbens, the ventral tegmental area, the amygdala, the hippocampus, and other areas.

Studies have shown reduced alcohol use in patients prescribed GLP-1 agonists. This was recently confirmed in a randomized, double-blind phase 2 trial demonstrating once-weekly low-dose semaglutide significantly reduced alcohol craving, heavy drinking days, and drinking intensity in non–treatment-seeking adults with AUD. Participants receiving semaglutide showed nearly a 50% reduction in alcohol consumption—an effect size equal to or greater than seen with FDA-approved medications for AUD, like naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram. Notably, these effects occurred at relatively low doses, were well-tolerated, and were accompanied by weight loss.

The Intestine as a Primary Reward Sensor

A major conceptual shift is recognizing the gastrointestinal tract functions as a sensory organ for reward. Calorically dense substances, including alcohol, carry reinforcing properties going beyond their central nervous system effects. Sugar, fat, ultra-processed foods, and alcohol engage overlapping gut–brain pathways.

However, GLP-1 receptor agonist medications apparently affect these gut-derived reward commands, decreasing both food and alcohol seeking.

Gut-derived hormones exert powerful, bidirectional effects on motivation. These hormones act directly on the same mesolimbic dopamine circuits that drugs do.

What is fascinating is that their effects are not limited to alcohol: preclinical and correlational data indicate possible benefits in decreasing use of nicotine and opioids, which makes sense as alcohol, cannabis, opioid, and nicotine use disorders cluster together genetically into one brain disorder. Although definitive GLP-1 randomized clinical trials remain limited, it might be very good news for patients, just like the invention of naltrexone, which also treats alcohol and opioid addictions.

Microbiome, Stress, and Immune Tone

Overlaying gut sensory and hormonal signaling is the gut microbiome. This is a complex system of microbes in the colon that help (or hinder) digestion and perform other functions as well. Everyone has a gut microbiome. Microbial metabolites also affect anxiety, dysphoria, and stress reactivity—core drivers of craving and relapse.

The intestine functions as a reward-sensing organ, peripheral physiology sets motivational drive, and central dopamine circuits are the final common pathway through which addiction is expressed.

GLP-1 receptor agonists simultaneously target multiple elements of this loop. Rather than opposing dopamine directly, they promote satiety, modifying the context in which dopaminergic learning occurs.

Clinical Implications and Conclusion

Connections between the digestive system and the brain have been postulated for 2500 years, but rediscovered recently. Specific mechanisms of gut-brain interaction have been identified. GLP-1 receptor agonist medications represent a conceptually-grounded, mechanism-based intervention. So we now have a promising new approach to treating alcohol and other addictions.

GLP-1 receptor agonists are not replacements for current medication treatments for AUD—but may soon become important additions. Their dual effects on weight and alcohol consumption highlight the shared biology underlying metabolic and addictive disorders. While more research is needed, the outlook is cautiously hopeful for the first time in many years.