970x125

Your team has pulled in data from a variety of sources, integrated it into a shared picture of what’s going wrong, and built a plan of attack. Great start. But now the next challenge begins: How do you keep that model aligned with reality as the situation continues to unfold?

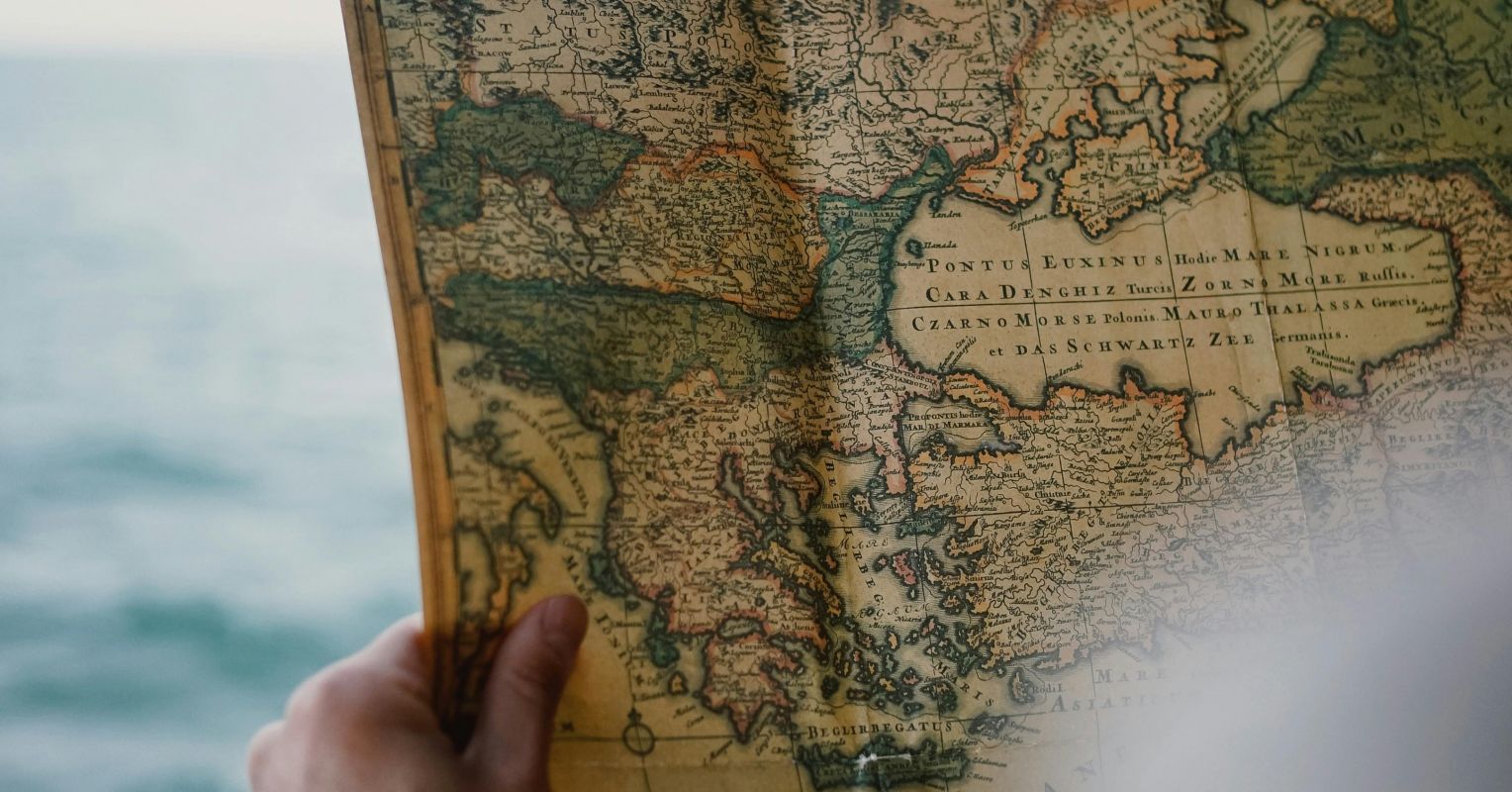

In fast-moving environments—intensive care units, wildfire operations, aerospace missions, and, increasingly, teams working with autonomous systems—mental models don’t stay current on their own. Reality keeps moving, and if your team’s understanding of the world doesn’t update with it, you end up with a map that no longer matches the terrain.

This widening gap between what we think is happening and what’s actually happening is known as model drift—a term borrowed from machine learning, where models lose accuracy when reality changes faster than they do. Human teams suffer the same pattern: Our shared understanding gets stale unless we actively refresh it [NOTE 1].

To see the danger clearly, imagine literal drift on the ocean. Before GPS, ship captains left harbor with a strong idea of their heading and position. But tiny, continuous errors—currents, wind, imprecise instruments—slowly nudged the ship off course. Hours or days later, those small deviations could place that ship miles from where they thought they were.

The same thing happens to teams, even high-performing ones. In fact, if you don’t actively work to routinely update your models of the world around you, the “default option” is that they will progressively become farther and farther away from an accurate map of reality. In other words, drift is the default.

In this post, we’ll look at three ways model drift can happen and explore what teams can do to counteract it.

Drift From Sensor Blind Spots

A three-reactor power plant with temperature sensors in only two reactors has an obvious blind spot. So does a business that doesn’t track inventory for its most fragile supply chain nodes, or a helicopter without a fuel gauge.

This sounds obvious, but blindness to change is one of the most common drivers of model drift. Teams tend to monitor the parts of the world they’re used to watching or that are easy to look at, not necessarily the parts that are most likely to shift.

High-performing teams address this by mapping where the highest-rate change (or its leading indicator) is likely to occur and then ensuring sensors (human or technological) are aimed at and sensitive to those changes.

Where best practices and proven models about what to look for are available, teams should make sure they are using them. For example, the Federal Aviation Administration dictates sensors that should be in place at airports to update the operating model of if a runway is clear or not, and airports should use them [NOTE 2], Where standard models are not available, teams can focus sensors on leading-edge indicators or look laterally from existing sensors to identify potential blind spots like that third reactor.

Drift From Communication Failures

Even sensors looking in the right direction won’t help a team update their mental model if they can’t communicate their findings. Communication failures drive model drift through two major routes: internal network failures and interference from outside sources in the environment.

In many hospitals, blood tests are sent from the patient to the lab using a pneumatic tube system, where they are run on centralized machines. Breakdowns in the tube system’s machinery, errors in where the blood tests are sent, or physical disruption of the samples during transit can all interrupt information flow and create distance between the mental model of the patient and their lived reality. Shortening the travel distance between sensor and processor—like bringing a small blood test machine to the patient’s bedside in critical cases—can decrease the opportunity for this kind of drift-causing network failure.

Additionally, sensors can be “tricked” by interference, like a compass pointing the wrong way to north in the presence of a strong magnet. Sometimes, this interference is predictable, and teams can build in a workaround to get high-quality information despite the interference. Blood tests looking at sodium levels, for example, can read abnormally low in the setting of high glucose levels, but a correction factor can be applied to get a more accurate reading [NOTE 3].

Drift From Low Sampling Rates

Even with good sensors and strong communication, model drift occurs when the situation evolves faster than the rate the model is updated—i.e., faster than their “sampling rate.”

In many standard hospital units, admitted patients get vital sign checks every four hours. Depending on the setup, it might be an additional hour before those results are entered into a computer and a doctor checks them, meaning that the fastest the team’s mental model of that patient can be updated is once every five hours.

If the patient’s condition deteriorates in minutes—anaphylaxis, arrhythmia, hemorrhage—the system’s sampling rate is far too slow to remain aligned with reality.

Intensive care units fight this by increasing sampling frequency—continuous vital monitoring, real-time displays for the team, and more frequent patient rounds. This higher sampling rate decreases the probability of cognitive drift for teams working with these patients, but ICU beds are limited resources.

The best-performing teams match their understanding of patients’ expected rates of change with the available resources—if they don’t have access to intensive care units, they position the patient close to the nursing station or break standard protocol and check on the patient more frequently [NOTE 4].

Detecting and Dealing With Drift

Whatever the cause—blind spots, degraded communication, or slow refresh—the first defense against model drift is simply acknowledging that it exists. Instead of automatically believing that the mental model they developed about a problem is just as accurate as when it first came together, these teams are always questioning if something changed in the world around them that makes that model not fit as well, and looking for blind spots that might make them miss critical details. Every team is susceptible to model drift—the world doesn’t stay still, and your mental model of it shouldn’t either.